One Pack of Plantain Chips is better than Half

A commentary on why Nigerian made goods are more expensive despite a currency devaluation

I am currently teaching a Macroeconomics class and last week we talked about the exchange rate and export competitiveness.

This is a short commentary on devaluation and export competitiveness for my class but also made available to my readers because it is interesting enough and it captures what is happening in Nigeria at the moment.

Export competitiveness is not the sole reason for a devaluation.

Currency devaluation tends to happen when the demand for a foreign currency like USD exceeds its supply. It is a correction that must happen because fundamental drivers of the currency have changed. Countries with external reserves can decide to allow an adjustment or postpone it by drawing down their reserves. Whichever option they choose, there is an adjustment.

Imagine a person whose income falls sharply but tries to maintain their lifestyle. It is only possible if they have enough savings (reserves) to support the lifestyle. At some point, if the income remains poor, they must make lifestyle changes. The management of the currency is not different.

In the Nigerian context, a devaluation is an adjustment that, more often than not, is forced. We do not devalue because of any coordinated strategy to improve competitiveness. In fact the default policy is to avoid a devaluation, and we destory our reserves in the process.

We devalue when the Central Bank has no more reserves to defend the currency.

I wrote about this in more detail in 2020.

Under the right conditions, a devaluation can support exports. If the conditions are not right, it can worsen competitiveness.

In Nigeria the conditions to export competitively are not right. Even though the Naira has lost around 74% of its value since May 2023, Nigerian goods are even more expensive to foreigners than before.

It is a myth to think that a devaluation automatically means goods are cheaper. The problem with Nigerian made goods is that there is no source of competitiveness locally. We do not have superior knowledge or technology, energy is not cheap and raw materials are not cheap. I doubt that we have any superior efficiencies to the rest of the world in the value chain of any product in Nigeria.

Even worse, energy and raw materials costs are directly indexed to the exchange rate. Once the exchange rate moves, energy and raw materials costs rise. Even labour costs have risen significantly if we use the minimum wage as a proxy.

What this means is that if policymakers are reckless on the monetary and fiscal front, there would be devastating impact on prices through the exchange rate channel. In essence, a devaluation can make things worse if the value chain is weak.

Let me explain why Nigerian goods are more expensive using a manufacturing company as an example.

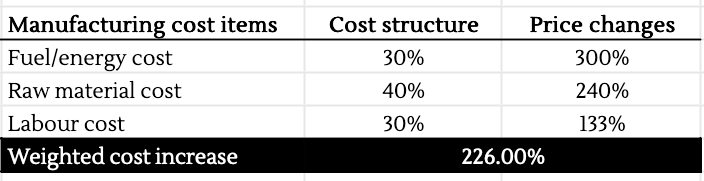

Let us assume that energy, raw materials and labour costs are 30%, 40% and 30% of production costs respectively.

I roughly estimate that energy prices have gone up by 300%, raw material costs have risen by 240% due to the exchange rate effect (in the official market) and labour costs have gone up by at least 133%.

The implication is that production cost has increased by around 226%. Such a significant change in costs will be passed directly to consumers, else firms go out of business. It is only small cost increases that firms can assume themselves.

Now let’s do a simple comparison of a manufactured good made in Nigeria versus a good made in the US. We will compare their prices to see how the Nigerian good is getting more expensive in real terms. This is called the real exchange rate, which is different from the exchange rate we see in the news.

By real terms, I mean the units of Nigerian goods a foreign good can buy. Here is a very basic explanation of this. Suppose one pack of plantain chips produced in the US can buy one pack of Nigerian plantain chips, then we are not doing badly and the rest of the world can decide to buy from any of the countries. But suppose that after some time one pack of US plantain chips can not buy one pack of Nigerian plantain chips anymore because the price has gone up significantly, then Nigeria loses competitiveness. Importers from the rest of the world will prefer to buy US plantain chips, afterall one pack is better than half, right? This is the true measure of competitiveness. Obviously, I am assuming that all other factors like the quality of plantain chips and tarrifs etc are the same in this example. Let’s consider some practical examples using three scenarios.

Scenario 1: When the exchange rate is constant but inflation is higher in Nigeria than in the US

In the table I have assumed a 15% inflation for Nigeria, 5% inflation for the US and an exchange rate of N500/$.

Clearly, you can see that that the US good was able to buy 1 unit of Nigerian good but by the fourth year only 0.76 units. Why? Nigerian goods have gotten more expensive.

To make the Nigerian good competitive, there can be a devaluation in the currency. But since there is no devaluation throughout, you can see that the 1real exchange rate (check the footnote for formula) appreciated from N500/$ to N380/$.

No country will want to buy Nigerian made goods. In fact, Nigerians will prefer to buy foreign made goods since they are getting relatively cheaper.

Scenario 2: When the exchange rate is devalued by the inflation differential between the US and Nigeria

In this scenario, once Nigerian policymakers see that the price of the Nigerian made good has risen faster than the the US made good, they can devalue the currency by the difference in inflation to make the real exchange rate constant at N500/$.

In this case, importers are indifferent. Nigerian goods are still competitive due to the devaluation.

Scenario 3: When the nominal exchange rate is devalued significantly but the manufacturer’s inflation rate rises significantly too

This scenario reflects our current reality. I looked at the change in price of an unripe plantain in Nigeria in 2021 versus 2024, which was +567%. So let’s assume that the price of our plantain chip reflects this, rising from N1k to N6.7k. In the US, prices have risen by 30% in that period. Finally, let’s consider different exchange rates for 2024.

Obviously, you can see the massive deterioriation in real terms. 1 pack of US plantain can only buy 0.19 pack three years later. And even though the Central Bank has devalued by 74% it is not enough to make Nigeria competitive. The real exchange rate has appreciated from N440/$ to N331/$.

Closing thoughts: macro stability and an efficient supply chain are non-negotiable if Nigeria wants to boost export competitiveness.

A significant exchange rate devaluation will not make Nigerian exporters competitive if their costs are rising as much or faster than a devaluation. To boost exports, input costs must be decoupled from the exchange rate and sharp devaluations should be avoided.

This commentary is purely on the basis that all other factors are the same, which isn’t true. The ports are bad, import tariffs are high, infrastructure is terrible, product quality is a big issue, and other numerous challenges make exports difficult.

But even if we assume that everything is fine, a devaluation is still not a silver bullet.

Nigerian policymakers cannot escape a disciplined monetary and fiscal policy stance that make prices stable. And even more, Nigerian policymakers cannot avoid doing the work of making the supply chain of Nigeria’s export industries more efficient compared to the rest of the world.

Only then can a deliberate devaluation of the currency be an export strategy.

Imagine that Nigeria’s inflation was 50% compared to US inflation at 30% between 2021 and 2024, if Nigeria devalued by 74%, there would be competitiveness. In that case, which is presented below, the real exchange rate will depreciate from N440/$ to N1,473/$. In simple terms, it means the Naira price of foreign goods will increase faster than the Naira price of domestic goods. That is when Nigerian goods will be cheaper (in relative terms)!

The formula for the Real exchange rate = Nominal exchange rate * Price of foreign good/Price of domestic good. It compares the Naira price of a foreign good to the Naira price of a local good. When the Naira price of a Nigerian made good is rising faster than the Naira price of a foreign good, then the real exchange rate is appreciating and Nigerian exporters will not be competitive.